Alexandra Lethbridge. Etch her name into your memory because this girl is going places. Ally, as she is also known, has got industry tongues waggling with her subtly layered project – The Meteorite Hunter, which she recently self-published.

The book – her first publication – was shortlisted for the First PhotoBook category in last year’s [2014] Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, a moment the Southampton-based photographer describes as one she won’t forget in a hurry. “I entered [the competition] on the basis that I was 100 per cent okay with not being shortlisted or winning,” she says when we speak on the phone. “I wanted the book to be out there, to see what might happen. I was shocked when I found out I had made the shortlist.”

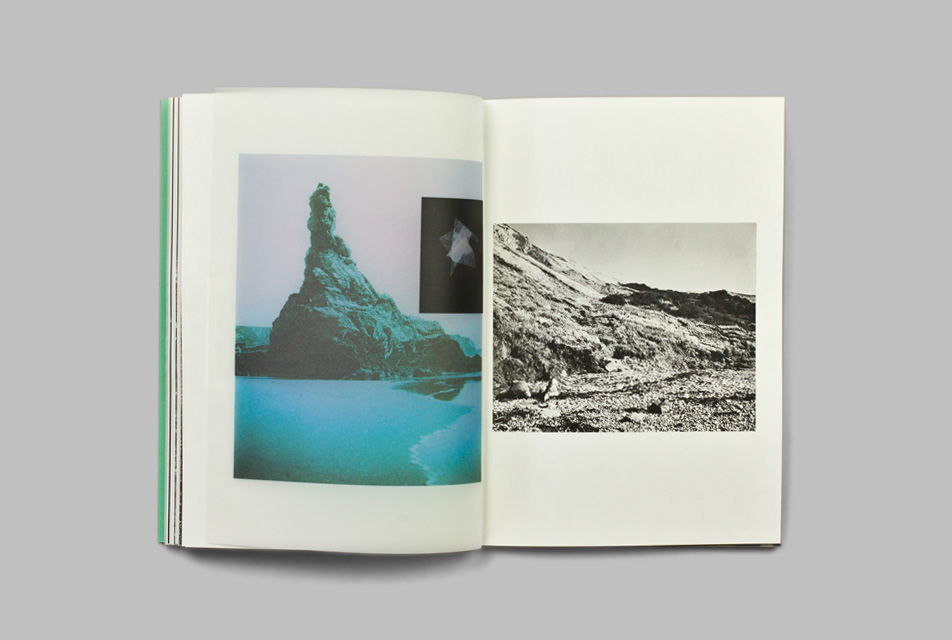

Describing the work as a “fictional archive about meteorites and the places they come from,” it is a series that plays with the notion of a meteorite hunter – a person who searches for and collects space rocks. In the book, we are presented with images of all manner of beautiful rocks in an array of shapes and textures, boasting exquisite colours. Some images are by the photographer, while others are found images sourced from places that include NASA. But the work is more than just a collection of spectacular rock images; it is about the hunt for the sublime in the ordinary, Ally explains, where a meteorite becomes a “metaphor for the fantastical, hidden within the everyday.”

The implication is, then, that these rocks are meteorites, and looking at the images you would assume they are; but, while one rock is in fact a real meteorite from space, the others are not, says Ally. They mostly come from museum gift shops, she reveals.

“I bought some [rocks] from a tiny gift shop in Lulworth Cove in Dorset for example, and they are the most beautiful things,” she says. “People have said to me, ‘ah, so that’s what a meteorite looks like’, and I’ve said ‘no, it’s nothing!’ Once you’re aware that one [rock] is ‘extra-terrestrial’ you start to look at everything [in the series] with the possibility that it could be sublime or fantastical… I hope that the viewer – for a moment – enters into this idea of reconsidering what’s around him or her, and what is ‘the norm’.”

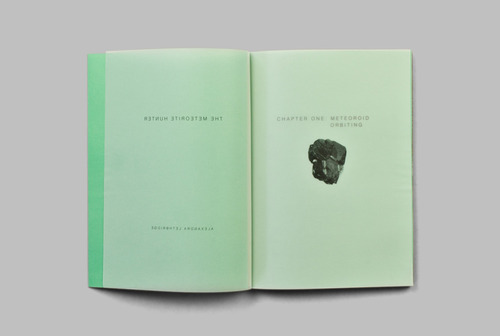

In this way, the series (and book) play with the idea of reality and fiction, encouraging the viewer to question what is real and what is not. Hidden captions concealed in panels at the beginning and end of the book reveal the source of each image, but the absence of text throughout (with the exception of chapter headings) helps to keep up the pretense.

“The book is a fictional archive that you walk through,” says Ally. “You have to go looking for the details that tell you what’s true and what isn’t… I’m not necessarily interested in misleading someone or trying to falsify something, it’s more about imaginary realms,” she adds. “I use lots of interventions in my work – ways of disturbing what you presume when you look at a photograph – but my interest lies more in ‘buying into’ this other realm than about trying to fool anyone.”

Ally, who graduated in 2014 from the University of Brighton with a Masters degree in Photography, explains she always wanted the book’s design to incorporate an element of “searching” and “hunting”. In addition to the hidden captions, Ally printed the images on tracing paper as well as on thicker paper stock, exploiting the different qualities of the papers to encourage the reader to look hard at what is being presented.

“The exhibition of the work [at the University of Brighton Gallery] featured tracing paper so I knew I would use it in the book,” she says. “I learnt about tracing paper’s weight, how it feels, how it turns, and what you can see through it… The sequencing and editing had to take into account [the fact that] if you can see through one page, what will be on the other side? So it wasn’t just a case of ‘this image comes after this one’, but about the layering. Producing the book was really complicated in that respect, but it was also enjoyable to make since it was meant to [be revealing], and to allow the viewer to see different things.”

Ally says she made many book dummies before settling on the final design, which uses Japanese binding and comes in four colours. Producing a small edition [of 100 copies] gave her the freedom to “make the book exactly how I wanted it to be,” although she was mindful of staying true to the essence of the work.

“I realise now that all the choices I make have to come back to the work,” she says. “It sounds obvious, but I hadn’t realised how much there is this element of doing what you like or what you tend to veer towards [when making a book], versus whether this actually plays into the integrity of the project. Initially, I wanted to create a hardbound book [and] I had a whole list of different binding techniques and approaches I could use; but these didn’t sit right when I was making the book. So I’ve learnt to stay true to what the book needs to be.”

Indeed, 2014 as a whole “has been a real learning curve,” says Ally, not least in terms of her practice. “For a long time my work has been in two places: half is film photography, landscape, straightforward; the other half is collage, and more experimental. The past year has been a [case of] figuring out how these things can come together.

“Being shortlisted for the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards has given me the confidence to move forward knowing that other people believe in my work as much as I do,” she adds. “I used to be quite shy, but it has made me think: ‘enough is enough – trust your instincts and go for it’.”